“It’s All in the Family,” in

Citizenship Booklet

c1951

In order to “be a man,” one must first establish the meanings and roles of the masculine and the feminine, and definite themselves in only one part of the binary. Brannon and David considered antifemininity, defined as, ”…the stigma of all stereotyped feminine characteristics and qualities…” to be the central organizing principle from which all other masculine demands derive.[^] Brannon and David wrote, “A ‘real man’ must never, never resemble women, or display strongly stereotyped feminine characteristics.”[^] In the hegemonic male’s performance of gender, it is just as important — if not more-so — to define one’s masculinity through the absence of feminine traits, than through the positive existence and performance of masculine traits. Unlike the other pillars in which a specific trait or activity was used to cultivate the aura of masculinity, the antifemininity dimension relies on and encourages binaristic gender roles. For the process of antifeminine masculinity to work, there must be an explicit separation of gender characteristics and roles.

The corpus of materials echo Elaine Tyler May’s thesis that the containment ideology of the Cold War was mirrored in the domestic lives of young Americans.[^] May argued that young adults were bound to the home because of political, ideological, and institutional developments that converged at the time.[^] Many of these same forces coalesced into inelastic gender roles, making the breadwinner/homemaker domestic family the ideal form.[^]

Many wartime publications, especially those of the Rosie the Riveter campaign, granted women typically masculine traits and focused on their ability to join the military and have a career. However women were still largely defined as being subservient to men, and there was a general understanding that they desire or even belong in the home. To the armed forces clergy at least, women’s military service did not provide them independence (via a career, income, training, or travel), but instead trained them to adjust to the men of the era. Because of their military service, the pamphlet states, women would be able to bend to the needs of the former male soldier.[^] The clergy represented the most socially conservative portion of the armed forces, but did serve as an important source in the military for finding answers to the questions and concerns about women’s service, relationships, and gender roles. Through these sorts of depictions, both explicitly and implicitly, gender differentiation was solidified, and masculinity was given the superior position in the binary.

The rejection of femininity has long been a staple of military masculinity, and is a concept deeply etched into the institution. This polar dichotomy was used as a tool for training and socialization: “The military uses its socially constructed polarity between masculine and feminine in order to use masculinity as the cementing principle that unites ‘real’ military men in order to distinguish from non-masculine men and women.”[^] Mary Wertsch, who researched American military socialization, wrote, “One of the things characterizing life inside the fortress is the exaggerated difference between masculine behavior and feminine behavior, masculine values and feminine values, Macho maleness is at one end of the spectrum; passive receptive femininity on the other.”[^][^]

The idea of antifemininity in the military was certainly not limited to the information and entertainment produced, nor was it limited to this specific time period. Many scholars of military masculinity have focused on the disavowal of anything feminine in the creation of masculinized soldiers. Aaron Belkin argued that the masculinity produced and circulated through the military served to smooth over contradictory moral and gender ideologies that are implicit in military service.[^] Belkin argued that the narrative of a disavowal of femininity allowed soldiers, as well as the general public, to overlook the contradictions and complications that military service placed upon men’s masculinity.[^] In practice, service often included homoerotic activities, paralyzing fear, physical debilitation, and a subordination to authority that cannot be questioned. This process of military masculinity also created a facade of perfect manhood that the public could trust. Because the narrative of service was free from the perceived weaknesses of femininity and composed of exemplary masculinity, men to serve without questioning processes which put them in close quarters with other men and stripped them of their autonomy.

Separated gender roles and descriptions created a discourse of what is acceptable and unacceptable. By illustrating differing and often dichotomous images and roles, these publications put forth notions of what was appropriate for men. Women, especially those illustrating traditionally feminine gender roles, were shown to be unfit for the workplace or subservient, and sometimes even demonized or demeaned them through female sexuality. Men and women were often shown in dichotomous roles, where women aided men in their military or capitalistic endeavors. These messages were sometimes explicit, while other times the ideologies behind them were embedded into narratives.

In some publications, especially in recruiting materials that target women, women were able to be celebrated and empowered through exhibiting traditionally masculine traits. When women exhibited traditionally masculine traits such as strength or courage, or gained employment, they were shown in a positive light. It was generally considered unacceptable for men to exhibit feminine traits, such as showing emotion or being non-aggressive or subservient. Although a number of these materials promote the idea of women joining the military or working in private industry, there was an understanding that these roles and manifestations of masculinity were only temporary, or that women could be easily distracted from them.

The differentiation between the Navy’s conceptions and assumptions about men and women can perhaps best be seen in the comparison between the comics Dick Wingate of the United States Navy and Judy Joins the Waves. The two comics, both published in 1951, begin with both protagonists unable to afford college to pursue the careers they desired. From there, the narratives varied greatly. Immediately after Judy joined the serve, she saw a male sailor walking through the train, and immediately clashes with another woman over the man’s attention.[^] The story focuses on her relationship with the sailor and her troubles with the other woman, leading up to Judy’s realization that the other woman was left behind on an island that was about to be shelled in training.[^] Judy alerted the sailors and they saved the other woman, and the story ended with Judy and the sailor presumably living happily ever after. Soon after joining, Dick is living his dreams and working on high-tech projects. Dick became engaged in a rogue smuggling and kidnapping investigation, and soon earned the attention of an attractive lounge singer who knew the kidnapped sailor’s whereabouts.[^] Dick came in and saved the sailor, and tackled the kidnapper just as he was about to shoot the lounge singer.[^]

Although both Dick and Judy found adventure and saved lives in the Navy, the focus of the stories is telling in the way the authors perceived the differences between men and women. Judy’s career aspirations were quickly abandoned for a love interest. The creators presumably felt that women would be more interested in a love story than a story about career success through the Navy. In many ways this assumption, along with the narrative throughout Judy Joins the Waves, aligns with the worldview that women may be interested in a career, but ultimately, they truly desire a husband and work in the domestic world. The assumption that women could work in times of crisis or prior to getting married, but not afterwards, was popular amongst men, and was a source of tension following WWII when many women were forced out of the workplace when men returned from abroad. Women increasingly fought against this notion, citing their abilities in the workplace during the war.

Some materials were much more explicit with the view that women were best suited for the domestic world, and were even misogynistic at times. This was especially clear in productions that were not meant for recruiting women. In a pamphlet distributed to clergy members of the armed forces, the piece portrayed an understanding of female enlistment that goes directly in the face of many empowering recruiting materials for women. In a question and answer section, the pamphlet read:

Q: Does service in the Armed Forces change a woman’s attitude towards having a home and family of her own in the future?

A: A woman’s natural instincts are for a home and family. Whether she serves a tour of duty in the military, works in an office or at a profession, or engages in some other endeavor, she never loses her interest in being a woman and a homemaker. A good many young people have met and have been married while in military service. Whether her marriage takes place then or later, chances are she will marry a former serviceman. She is likely to be a better wife and mother because of her military training. She will better understand the importance of daily routine and discipline, having learned in the military. She and her husband will have the common interest of past military life, and a shared mutual relationship which will make their marriage relationship much closer. Then, too, women everywhere are sought out when there are tasks to perform that women do exceptionally well. So it is in the military. If there’s a Sunday School class to teach, a nursery nearby or entertainment to plan, the officers and enlisted men alike turn to the woman in their ranks because she is a woman and can do that job particularly well. All of these contribute to her future success and happiness as a wife and mother.[^]

Other texts were openly misogynistic, and demonized women by illustrating female sexuality as dangerous or threatening. One WWII-era comic, This is Ann, warned soldiers of the dangers of malaria through the use of a feminized mosquito named “Ann.” The comic puts out a clear, though unspoken, link between malaria carried by mosquitoes and venereal disease carried by women. The cover claims that Ann is “dying to meet you,” as she stands primping herself.[^] The next page advances the sexualized image of Ann, viewing her in the same pose, but this time through a keyhole, adding voyeurism to the imagery of feminization and sexualization.[^] Along with her apparent beckoning to the voyeuristic reader, the pamphlet emphasizes that she really is inviting – “Ann really gets around” – the caption reads.[^] Ann’s sexualized identity and loose morals are solidified by adding, “Ann moves around at night, anytime from dusk to sunrise (a real party gal), and she’s got a real thirst.”[^] By equating the spread of malaria with the spread of venereal disease, the comic demonizes female sexuality, and promotes the idea that women who are openly sexual are dangerous or have hidden motives. Many anti-VD posters and pamphlets also put forth this narrative, but This is Ann stands out above the others for forcibly inserting female sexuality into non-sexual matters.

These examples depict a process where femininity is defined as inferior or subservient, while masculinity is prized and positive. The military materials I examine rarely explicitly demean men exhibiting femininity. Instead, they generally offer positive support of masculinity, while constructing femininity in women as the second gender. There were very few times when artist’s renderings of men showed them as being anything less than a prime male form. In one glaring exception, however, a character was feminized, demeaned, and insulted as a method to discourage reckless behavior.

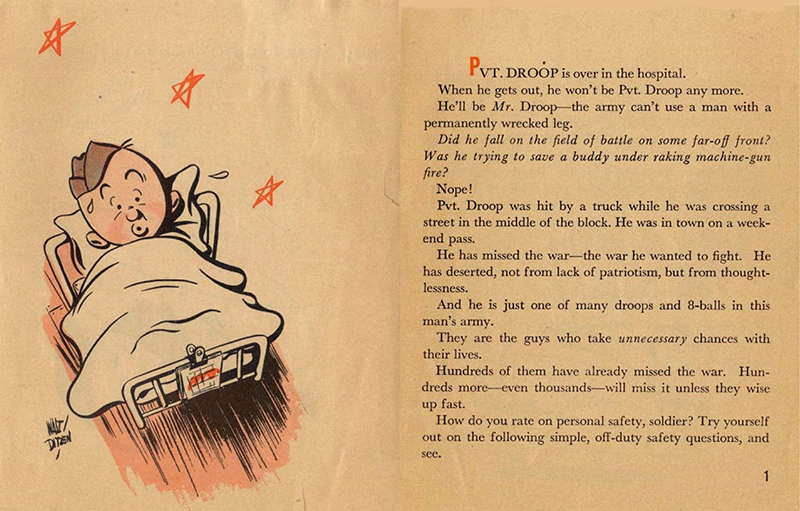

The 1944 Army pamphlet, Pvt. Droop has Missed the War!, warns soldiers of the risky behavior they must avoid in order to remain a part of the US military.[^] The publication shames Pvt. Droop for acting dangerously while on leave, rendering him inactive for the rest of the war. The pamphlet shames him in writing, as well as through unmasculine depictions, as if to connect discouraged behavior with his body type and appearance. He is depicted as child-like, with a large head and a small, undeveloped body. This unmasculine depiction is a stark contrast from the broad shoulders and bulging muscles displayed in most soldier illustrations. The name “Droop” is also loaded, and signifies a lacking virility and physical presence.[^] Pvt. Droop was used as an example of a lack of masculinity, one that could be avoided by soldiers if they aced responsibly.

In instituting male superiority, the materials also draw upon some classically held ideas about men preferring male children. This idea is not only underwritten by ideas of male superiority and advantaged property inheritance, but also through the idea that a man was much better suited to be a father for a son, rather than a daughter. Time of Decision was an Army ROTC comic book about a man who uses his ROTC training to advance in the business world and become an ideal breadwinner. His wife is pregnant with their first child when they hear word that war has broken out in Europe. He advises her, “Don’t worry about it honey, just take care of yourself and make sure you present me with a husky son on schedule.”[^] Not only did the man request that he would be “presented” with a son, but also a masculine son. By requesting a “husky” son, he was not only asking for a sufficiently medically healthy son, but also a son that fit some of the ideas about what comprised a man’s health, like a strong build and a certain amount of mass. The comic ends happily – his wife gave birth to a husky son right on schedule. Similarly, Henry, the protagonists’ neighbor in It’s All in the Family, a trope about the importance of family in the fight for the American way of life in the face of Communism, danced around the waiting room when he learns his wife gave birth to a boy.[^]

The masculine dimension of antifemininity can be seen through these pieces, though not always exactly as David and Brannon defined it. David and Brannon viewed this as a largely social process whereas men disavow femininity in their own lives, and police peers on the same lines. Although much of the “Inexpressiveness and Independence” corpus can be interpreted in this manner, there are few other examples where individual men explicitly reject characteristics that may be interpreted as feminine. Rather, in the majority of the corpus, masculinity and femininity are painted in very different tones, and masculinity is given a clear endorsement. Men are more celebrated as they are shown as more masculine, while women are more subservient and demeaned as they are more feminine.